- Home

- Powerful Learning

- Powerful PostsApril 14, 2025

How to Study Effectively

March 31, 2025How to Study Effectively

- Powerful Learning Categories

Teaching is a highly complex activity that is continually evolving. Learning theory and brain research has increased the efficacy of teaching and instruction in helping students to know what the learning target is, understand the concepts in the outcome and utilize authentic assessments that informs students about their learning.

The following strategies are known to have a “high impact” on learning based upon the research of numerous researchers including John Hattie. As new research emerges, it will continue to inform future practice.

Golden Hills encourages the implementation of powerful strategies in all classrooms. It is important to note this list does not include all possible strategies that teachers can incorporate into the classroom.

Assessment in Golden Hills is comprised of a balance between summative and formative measures and tools. Use of descriptive feedback, clear targets and exemplars are integral to the assessment process in Golden Hills.

Grading occurs within the context of sound assessment practices in order to achieve accuracy in reporting student understanding of the curricular outcome. Assessments need to assess what they say they will measure in order to be valid and reliable.

Evidence of students learning is collected through a variety of methods including conversations, observations and products. The summative grade is then assigned and communicated using grading practices that align with the “Golden Hills School Divisions Seven Principles of Assessment”.

These practices serve to establish, sustain and grow student learning and confidence as well as accurately communicate what the students knows, understands and is able to do.

Assessment in Golden Hills is comprised of a balance between summative and formative measures and tools. Use of descriptive feedback, clear targets and exemplars are integral to the assessment process in Golden Hills. Grading occurs within the context of sound assessment practices in order to achieve accuracy in reporting student understanding of the curricular outcome. Assessments need to assess what they say they will measure in order to be valid and reliable. Evidence of students learning is collected through a variety of methods including conversations, observations and products. The summative grade is then assigned and communicated using grading practices that align with the “Golden Hills School Divisions Seven Principles of Assessment”. These practices serve to establish, sustain and grow student learning and confidence as well as accurately communicate what the students knows, understands and is able to do.

Summative assessment is defined as assessment designed to collect information about learning to make judgments about student performance and achievement at the end of a period of instruction to be shared outside of the classroom (AAC).

Learning is an ongoing process and does not end because of a summative assessment. If your student has demonstrated that they have mastered the outcome then you can turn the summative assessment into a formative assessment based on the most recent evidence.

An assessment can be either summative or formative depending upon what you do with it. If the assessment is used to “sum up” or describe what the student knows or can do, then it is summative. If the assessment is used as part of learning and students incorporate the feedback to keep learning improve a task before marking, then it is formative.

Assessment as Learning is the ongoing self-assessment by students in order to monitor their own learning. In Golden Hills we have included this idea within the AFL definition and within the metacognition section of this document.

Formative assessment that result in an ongoing exchange of information between students and teachers about student progress toward clearly specified learner outcomes. (AAC)

Formative assessment can be seen as a process that relies on several measures over time. It is viewed as a process rather than a singular event (Bennett, 2011). Information collected through the use of formative assessment is used to further student learning (Ayala, 2005). Teachers create instruction based on evidence gathered through formative uses of assessment. These formative interactions are designed to encourage thought on the student’s part (Black & William, 2009). Teachers use information from these interactions in order to make decisions surrounding the curriculum and the direction of learning. They determine whether to move forward, how to move forward and where to encourage student focus. This view focuses on the process of developing and changing instruction to match student needs.

Golden Hills has focused on improving student learning through developing teacher practice in attending to ongoing “minute-by-minute and day-to-day formative assessment” (William, 2011, p. 27). Formative assessment “encompasses all those activities undertaken by teachers and /or students, which provide information to be used as feedback to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged” as cited in William, 2011. William states “An assessment functions formatively to the extent that evidence about student achievement is elicited, interpreted, and used by teachers, learners, or their peers to make decisions about the next steps in instruction…” (William 2011, p. 43). In order for teacher and learners to determine next steps, it is imperative that teachers determine “where students are at in their learning, where they are going and how to get there”. The AFL strategies implemented in Golden Hills help teachers to plan with clear goals linked to curriculum, as well as understand how to provide extensive descriptive feedback during the learning. Hattie (2009) identified in his meta-analysis research that “feedback” is ranked as having a high impact on student learning.

Golden Hills’ achievement results have improved by integrating effective assessment for learning practices.

Golden Hills has identified the following key components of “Assessment for Learning” to be implemented during the instructional process to improve teaching and learning.

| Curriculum Essentials |

|

Effective Questioning |

|

| Effective Feedback |

|

| Exemplars |

|

| Rubrics |

|

| Student Goal Setting |

|

| Peer and Self-Assessment/

Feedback |

|

| Differentiation |

|

| Triangulation of Data |

|

| Additional Resources

|

For additional formative assessment strategies and descriptions go to:

Tools for Formative Assessment – Techniques to Check for Understanding – Processing Activities – http://www.levy.k12.fl.us/instruction/Instructional_Tools/60FormativeAssessment.pdf Brookhart, S. (2010). Formative Assessment Strategies for Every Classroom (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Dodge, J. (2009). 25 Quick Formative Assessments for a Differentiated Classroom. New York: Scholastic Inc. Moss, C. & Brookhart, S. (2009). Advancing Formative Assessment in Every Classroom-A Guide for Instructional Leaders. Alexandria: ASCD. William, D. & Leahy, S. (2015). Embedding Formative Assessment – Practical Techniques for K-12 Classrooms. West Palm Beach, FL: Learning Sciences International. Effective Grading Practices: Davies, A. (2011). Making Classroom Assessment Work (3rd ed.). Courtenay, BC: Connections Publishing O’Connor, K. (2012). Fifteen Fixes for Broken Grades – A Repair Kit (Canadian ed.). Toronto, ON: Pearson O’Connor, K. (2018). How to Grade for Learning – Linking Grades to Standards (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Schimmer, T. (2016). Grading From the Inside Out – Bringing Accuracy to Student Assessment Through a Standards-Based Mindset. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press Schimmer, T. (2012). Ten Things That Matter from Assessment to Grading. Toronto, ON: Pearson Canada Inc. William, D. (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment. Bloomington: Solution Tree. |

Timely and concise feedback provides students with information about what they know or don’t know and is used, by teachers, to direct further instruction. Teachers can use this feedback to help students bridge the gap between what they know and what they need to know (Ayala, 2005). As students use feedback, they become capable of building upon their own learning and develop enhanced metacognition and increased motivation (Brookhart, 2012). “When teachers seek, or at least open to, feedback from students as to what students know, what they understand, where they make errors, when they have misconceptions, when they are not engaged-then teaching and learning can be synchronized and powerful. Feedback to teachers helps make learning visible” (Visible Learning, 2009, p.173). The most effective feedback provides information to students about their tasks and how to do it more effectively (Hattie & Timberley, 2007).

| Overview / Implementation |

|

Teaching mindfully and with the intent to support the success of all learners moves us away from seeing and teaching students as a unit to responding to them as individuals. According to Carol Ann Tomlinson in “Differentiation and the Brain” (2011 p 9), differentiation is not a set of strategies, but a way of thinking about teaching and learning. Her model of effective differentiation stems from research on how people learn and how strong teachers teach. This learner centered model asserts that

Key reasons to differentiate are that it improves students’ access to learning, motivates them to learn and makes learning more efficient. Applying “differentiated instruction” can help address the needs of academically diverse learners in our increasingly diverse classrooms.

| Overview/Implementation |

| Key Principles |

|

| Basic Steps in Differentiation |

|

| Elements to Differentiate | Content

Process

Product

Affect/Environment

By differentiating in these areas, student variance in terms of readiness (proximity to learning goals), interests (for particular ideas, topics or skills) and learning profile (preferences for approaches to or modes of learning) can be accounted for. As a result, the likelihood of academic success and maximum student achievement can be reached. |

| Instructional and Management Strategies | Teachers can reach out differently to students while keeping all students focused on essential outcomes.

Content

Process

Product

|

Powerful Learning classrooms are places where thinking is valued, visible and actively promoted as part of the daily routine.

Thinking is part of the lessons that are designed, the questions that are asked, and the connections that are made outside the classroom. Thinking is intentionally woven throughout the learning experience.

In other words, learning is a consequence of thinking and the primary goal is the advancement of thinking.

Designing Powerful Learning incorporates opportunities for students to develop creativity in their classrooms. Creativity is a core competency defined by Alberta Learning as the ability to apply creative thought processes to create something of value. Moving away from scripted lessons to asking questions that encourage critical and creative thinking helps our students to think in both divergent and convergent ways, analyzing and evaluating as they learn. Drapeau states that both divergent and convergent thinking are necessary for creativity. (Drapeau, 2014) “A student uses divergent thinking to generate different solutions to a problem or challenge and then uses convergent thinking to decide which one will provide the best results”. (Drapeau, 2014)

Peter Gamwell (2018) talks about three imperatives that foster creativity. These imperatives include recognizing there is a seed of brilliance in everyone, adopting a strength-based approach and creating a culture of belonging.

“The creative process includes elaborating on the initial ideas, testing, and refining them and even rejecting them.” (Drapeau, 2011, As cited in Drapeau, 2014, p 2) This results in innovation which is one of the core competencies is defined by Alberta Learning as the capacity to create and apply new knowledge to create new products or solve complex problems. The importance of fostering creativity is recognized and the role teachers have in setting this up is also understood.

To see Creativity and Innovation in Golden Hills, go to this Powerful Story.

| Overview / Implementation | |

|

|

Metacognition awareness is the ability to notice one’s own thinking. This involves both awareness and understanding of one’s own thought process, in other words “Thinking About Thinking”. It is the ability to monitor, evaluate, and plan for one’s own learning. (Flavell 1097, as cited in Fisher et.al. 2018 pg. 115). Research shows that metacognition can be taught in order to help students improve their own learning.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation |

| Metacognition |

1. identify possible solutions and plan how to implement the most likely one 2. implement the solution 3. assess its effectiveness and make adjustments if necessary 2

1 Lovett, M. C. (2008). Teaching metacognition [PowerPoint presentation]. Retrieved fromhttp://net.educause.edu/upload/presentations/ELI081/FS03/Metacognition-ELI.pdf

|

Thinking routines as outlined by Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church and Karin Morrison (2011) in “Making Thinking Visible”, strive to help students achieve deeper understanding through the use of thinking routines and effective questioning. To think or understand “deeply” means “there is a focus on developing understanding through more active and constructive processes” (Ritchhart et al. 2011, p. 7). When students develop a greater awareness of “how they think”, they become independent learners capable of directing and managing their own thinking and learning. Ritchhart states that thinking routines act as tools for promoting thinking, as well as provide structures and patterns for thinking. Golden Hills teachers strive to build student understanding by making thinking visible in their classrooms. Routines for introducing learning, synthesizing and organizing ideas and digging deeper into ideas are outlined.

| Overview / Implementation | |

| Thinking Moves

|

Ritchhart et.al describes key thinking moves that are involved in different kinds of thinking in order to understand. These include:

|

| Ways to Make Thinking Visible | Ritchhart et al. (2011) has identified three ways to make thinking more visible. “Through questions, teachers can model their interest in the ideas being explored; help students to construct understand and facilitate the illumination of students’ own thinking to themselves”. (Ritchhart, Church & Morrison, 2011, p. 31) |

| Thinking Routines | Three clusters of thinking routines make thinking visible according to Ritchhart et al. (2011). Ritchhart defines thinking routines as any procedure, process or pattern of action this is used repeatedly to manage and facilitate the accomplishment of specific goals or task.

1. Routines for Introducing and Exploring Ideas (i.e. See-Think-Wonder, Chalk Talk) 2. Routines for Synthesizing and Organizing Ideas (i.e. Headlines, CSI: Color, Symbol, Image) 3. Routines for Digging Deeper into Ideas (i.e. What Makes you Say That, Step Inside) |

Critical thinking engages students in exploring provocative questions or challenges and encourages students to investigate, reflect, create and share their understandings. When someone is thinking critically they are assessing or judging the merits of potential options based on a set of relevant criteria.

In order to foster critical thinking, students need opportunities to build upon their prior knowledge, communicate with peers, develop knowledge and skills to analyze information and draw their own conclusions in an engaged classroom.

Golden Hills has recognized the importance of infusing critical thinking into our classrooms. Students are invited to think critically or reason using a set of criteria. When students are offered a critical challenge and encouraged to engage in critical inquiry, increased engagement and deeper learning can be achieved. Garfield encourages “teachers to activate learning about a topic by involving students in shaping questions to guide their study, giving them ownership over the direction of these investigations and requiring that students critically analyze and not merely retrieve information.” (Gini-Newman & Gini-Newman, p. 35). In this way, according to Garfield, a shift occurs from covering curriculum to students uncovering the curriculum”. The content of the curriculum is “problematized” which then leads to an investigation and discovery connected to the real world. Through this type of investigation students draw conclusions, make decisions and solve problems.

The Critical Thinking Consortium is a great place to for resources for Critical Thinking.

| Overview / Implementation | |

| Developing Intellectual Tools |

(Case, 2005) |

| Effective Questioning |

|

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Oral Discussion Strategies |

|

| U-Shaped Discussion | Instead of an adversarial debate format, this strategy encourages students to see the merits of all sides and to recast binary options as positions along a continuum. Students endorse their position while listening to others to determine the most defensible stance. |

| 4 Corners | Students are required to take a position by moving to the corner of the room labelled with their position and discussing the reason for their position with one student with the same and one student with a differing position. |

| Tag Debate | Similar to a traditional debate, but those in the ‘speaker’s chair’ can be tagged out and another student can move in to add another argument to the conversation. |

Perspective Taking Strategies |

|

| 3-Step Interview | In groups of 3, students are assigned a perspective or role. They then each develop questions and interview the other roles. This requires that students frame powerful questions, listen and record important information, and respond to questions considering a particular perspective. |

| Redraw an Image | Students are asked to examine an image, determine the perspective from which it was created, and use evidence and inference to redraw how the image would appear differently from an alternate perspective. |

| Step into the Picture | In groups, students examine an image or text. Groups are invited to tell what happened in the time before or after this image – perhaps 3 minutes, or 3 days, or 3 years. This can be performed as a skit. |

Making Judgement Strategies |

|

| Value Time Line | In addition to placing events in chronological order along a time line, students rate the significance or impact of events by placing them above or below the line. |

| Opportunities

Challenges and Wonder |

We often encounter things that seem to have merit, but also raise some concerns. To make a reasoned assessment, have students consider the Opportunities, challenges, and Interesting/Wonderings of an idea or proposal. |

| Ranking Ladder | Have students rank the most important or significant contribution to an issue, topic, or event. As learning progresses, have students revisit their ranking and revise it based on new evidence. |

| Fulcrum | Use a balance scale to have students display which of two options has a greater impact, better represents, or which direction an event had on an outcome. |

| Dashboard | Have students display their position on an issue or topic by selecting where they fall on the dashboard continuum. Students are given time to reflect and readjust their dial as learning progresses. |

| Pie Chart | When given a number of factors, students create a pie graph containing each factor and the size of each slice (Factor) represents the degree to which each factor contributes to an event or issue. |

Generating Ideas Strategies |

|

| Five Senses | Students make an abstract concept or idea more real by brainstorming connections to your five senses. |

| Create a Powerful Headline or Question | In this strategy, you are required to use your creativity to summarize the main ideas or find out more about a source. |

| Placemat | Students work collaboratively to weigh options and come to a consensus. Often used to summarize large amounts of information or give everyone a chance to share their ideas. |

The Instructional Tools section describes a variety of high yield, evidenced based strategies and practices that are utilized when designing Powerful Learning experiences for students.

These strategies help to make the learning relevant and support students as they extend and apply knowledge. Through using these tools, students can become more efficient and flexible in using what they have learned.

Academic Vocabulary summary sheet

Academic Vocabulary summary sheet

Marzano and Pickering (2005) reported that when students have general knowledge of the terms that are important to content taught in school, achievement is significantly improved. One of the most crucial advantages that teachers can provide, particularly for students who do not come from academically advantaged backgrounds, is systematic instruction in important academic terms.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation |

| Academic Vocabulary | Explicitly teaching academic vocabulary involves 6 basic steps. Attending to all steps ensures best results.

|

Cues and Organizers – Advanced Organizers summary sheet

Cues and Organizers – Advanced Organizers summary sheet

The use of cues and organizers provide students with a conceptual framework to hook new learning on to and they enhance student’s ability to retrieve, use and organize what they already know about a topic. The use of a variety of graphic organizers throughout the learning provides opportunities for students to extend and apply knowledge.

Advance organizers are stories, pictures and other introductory materials or tasks that set the stage for learning (Dean, Hubbell, Pitler & Stone, 2012).

Post organizers are tasks completed at the end of learning that summarizes or captures the key ideas.

Overview / Implementation |

|

| Graphic Organizers | Examples of effective graphic organizers include:

|

Similarities and Differences summary sheet

summary sheet

The set of instructional strategies that cluster around identifying similarities and differences involve students in comparisons, classifications, metaphors and analogies. These strategies help students move from existing knowledge to new knowledge, concrete to abstract and separate to connected ideas. Twelve studies were reviewed in a meta-analysis, 2010, conducted by McREL researchers. The effect size of these strategies was .66 which is equivalent to a 25 percentile point gain (Dean, Hubbell, Pitler & Stone, 2012). This indicates that students benefit from the explicit instruction in processes which use similarities and differences.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation |

| Comparing | Students will look at two or more elements and look for similarities and differences between them. A great graphic organizer for this is a Venn Diagram. |

| Classifying | The process of organizing things into groups and labeling them according to their similarities. |

| Metaphors | The process of identifying a general or basic pattern in a specific topic and then finding another topic that appears to be quite different but has the same general pattern. It provides an anchor for new abstract learning through the intentional teaching of metaphors to focus on how items are similar on an abstract level. |

| Analogies | The process of identifying relationships between pairs of concepts and pairs of relationships. It guides us to see relationships between things that seem dissimilar on the surface. Ex) A is to B as C is to D.

Resource: Page 90 of The Highly Engaged Classroom Resource: The Sourcebook for Teaching Science provides an online guide for how to teach science through the use of analogies. http://www.csun.edu/~vceed002/ref/analogy/analogy.htm |

Nonlinguistic Representation summary sheet

Nonlinguistic Representation summary sheet

Nonlinguistic representations have been found to provide students with useful tools that merge knowledge presented in the classroom with ways of understanding and remembering knowledge (Jewitt, 2008). Nonlinguistic representation strategies are ones which help students represent understanding and elaborate on that knowledge using mental images or imagery. Nonlinguistic representations involve imagery, creating pictures and engaging in kinesthetic activity. Research has found this to be a powerful strategy because it taps into a student’s natural tendency for visual image processing. This strategy helps students to construct meaning of relevant content and skills and have a better capacity to recall it later (Medina, 2008). Studies in Beesley and Apthorp’s, 2010, analysis indicated that the impact of using nonlinguistic representations can multiply when teachers and students use the strategy in combinations with other strategies.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation | |

| Physical Models | Hands on tasks to create concrete representations of knowledge. | |

| Mental Imagery | Students are asked to create a mental picture of the information to help them make sense of what they are learning to and to help store it in long term memory.

Incorporate sounds, smells, tastes and visual details as part of the overall mental picture. |

|

| Creating Pictures | Students draw or color pictures that represent knowledge. Using pictures helps students to represent their learning in personalized ways. An example could be “draw what it means to you.” | |

| Kinesthetic Activity | Students engage in physical movement associated with specific knowledge to generate understanding of content/skills. When students move they create more neural networks in the brain and learning is enhanced.

Examples:

|

|

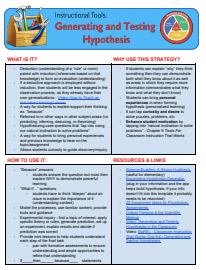

Generating and Testing Hypotheses summary sheet

Generating and Testing Hypotheses summary sheet

Generating and testing hypotheses deepens student knowledge because it requires the use of critical thinking skills when analyzing and evaluating. Problem solving, experimental inquiry and investigation are incorporated to generate and test a hypothesis. Generating and testing hypotheses applies knowledge through the use of two thinking processes. One of these processes is deduction which involves using general rules to make a prediction about a future event or action. Induction is the second thinking process, which involves making inferences based upon knowledge that the student already has. This involves drawing new conclusions or identifying rules based upon observations. This strategy enhances students understanding of and ability to use knowledge by engaging them in the mental process required for making and testing hypothesis.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation |

| Generating and Testing Hypotheses | Hypothesizing includes predicting, inferring, deducting and theorizing. By engaging them in mental processes that involve making and testing hypotheses, students’ understanding and ability to use knowledge is enhanced. This moves them beyond “right answer learning.”

Classroom Practices:

2. Ask students to explain their hypotheses and their conclusions helps students deepen their understanding of the principles they are applying. |

Summarizing and Notetaking summary sheet

Summarizing and Notetaking summary sheet

Summarizing and note-taking are essential elements of learning. Summarizing is the process of distilling information down into its most essential points to increase understanding, memorizing, and learning what is relevant. Note-taking is the process of capturing key ideas through writing, drawing, etc. These are essential strategies because they involve higher-order thinking skills. Note-taking strategies are not intuitive which means that students benefit from explicit instruction in note-taking, particularly those that are guided by the teacher and are structured.

| Strategy | Overview / Implementation |

| Summarizing Strategies |

Rule based summarizing strategy● Take out material that is not important to understanding ● Take out words that repeat information ● Replace a list of things with one word that describes them ● Find a topic sentence or create one Use summary frames● A series of questions designed to highlight the critical elements of a specific text pattern ● There are six frames

Teach student reciprocal teaching● There are four roles

Click here to learn more about Reciprocal Teaching. |

| Note-Taking Strategies | Give students teacher prepared notes

● Show the organizational structure, model Teach a variety of note-taking formats ● Webs, words, pictures, computer generated notes, outlines Provide opportunities for students to revise their notes and use them for review ● Leave spaces in notes for revisions as learning takes place ● Provide feedback during review to allow for growth in the skill development Narrow the margins of a document, like a story or article, to allow room for additions, corrections, thoughts, or questions. |

Effective Questioning summary sheet

Effective Questioning summary sheet

Questioning has been found to be the second most dominant teaching method after teacher talk, with teachers spending 35-50% of teaching time posing questions (Hattie, 2009, p. 182). Questioning is a powerful strategy for teaching concepts, building comprehension and helping students to assume an inquiry stance towards learning. Asking questions to foster an inquisitive stance helps students to be open to new ideas. Most questions that teachers ask are questions they already know the answer to (guess what is in the teachers head types of questions) as cited in (Hattie, 2009. P. 182). The goal is to ask questions that encourage students to think. The importance of questions that will propel learning and build curiosity are highlighted in Ritchhart et.al’s work (2011). A balance of the types of questions and the use of questions that will foster inquiry and critical creative thinking are encouraged in the implementation of Powerful Learning.

When implementing Powerful Learning, inquiry and critical thinking are fostered through a balance of the types of questions how they are asked. The majority of questions asked by teachers are low-level questions that require students to recall facts. There is one correct answer to these questions and students play a game of “guess what is in the teacher’s head” (Hattie, 2009. p. 182).

The importance of questions that will propel learning and build curiosity are highlighted in Ritchhart et.al’s work (2011).

Powerful questions emerge from our goals and expectations for learning and may not always be planned in advance.

Ritchhart (2015, pg.221) describes five types of questions:

Click here for a handout regarding question typology.

Questioning has been found to be the second most dominant teaching method used in classrooms after teacher talk, with teachers spending 35-50% of teaching time posing questions (Hattie, 2009, pg. 182).

Effective questioning criteria:

| Overview / Implementation | |||||||||||||

| Key Ideas

|

|

||||||||||||

| Powerful Questioning and Talk | Powerful Learning is supported by powerful questioning and conversations. The “accountable talk” (Hattie, et. al.) strategy helps to build these skills. Conversational moves and prompts are modeled by the teacher and then integrated into student conversation.

*Retrieved from the companion website for Visible Learning for Mathematics, Grades K-12: What Works Best to Optimize Student Learning by Hattie, et.al) 2017. |

||||||||||||

| Levels of Questions | Address all three levels of questions:

1) Gather – collecting information, fact finding, recall 2) Process – comparing, analyzing 3) Apply – evaluate, judge, application Constructive Questioning: (Ritchhart, Church & Morrison, 2011)

What are good questions?

How are good questions created?

What are teacher’s responsibilities?

|

||||||||||||